Why LLMs Forget - And How Developers Make Them Remember

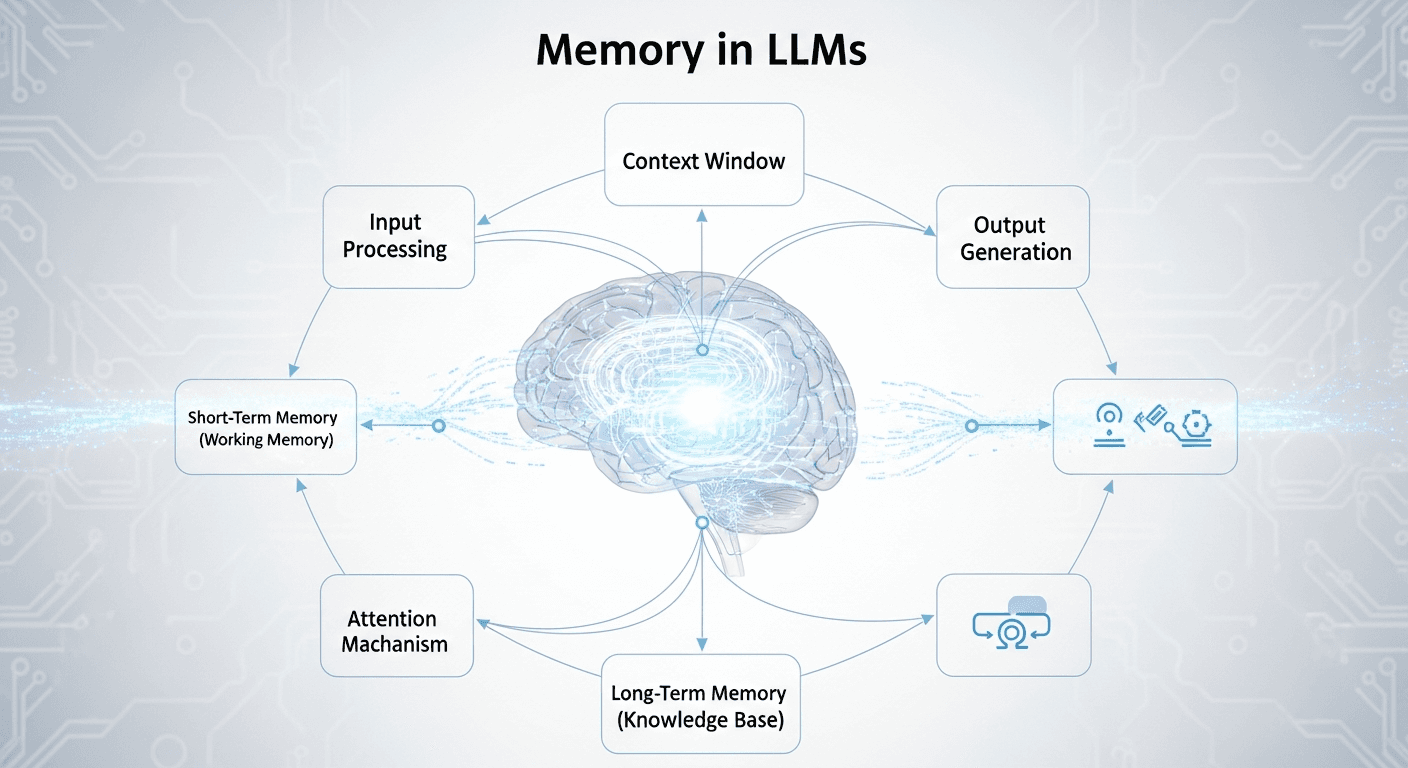

Large Language Models (LLMs) have revolutionized Generative AI, powering everything from sophisticated chatbots to intelligent content creation tools. However, a fundamental characteristic of these powerful models often leads to a critical misconception: LLMs inherently lack memory. This absence poses a significant challenge for building truly conversational and continuously intelligent AI applications. Understanding how LLMs operate without intrinsic memory and how developers ingeniously engineer memory solutions around them is indispensable for anyone working with Generative AI.

This post delves into the core mechanisms behind LLM functionality, dissects the challenges posed by their stateless nature, and explores the innovative techniques used to imbue them with both short-term and long-term memory, enabling richer, more coherent, and personalized AI experiences.

The Stateless Nature of LLMs at Inference

At their core, Large Language Models function as highly complex

mathematical equations. During inference (The process

where a trained model generates output based on new input) an LLM can be

conceptualized as a parameterized math function:

y = f_θ(x).

-

f: Represents the intricate underlying mathematical function, typically a deep neural network architecture. -

Theta (θ): Denotes the billions of fixed parameters (weights and biases) that define the LLM's vast knowledge and learned behaviors. These parameters are established during the extensive training phase and remain static during inference; they are not altered by user interactions. -

x: Represents the current input provided by the user, often referred to as the "prompt." This is a variable input, unique to each interaction. -

y: Represents the output generated by the LLM in response tox.

LLMs are inherently stateless. A stateless system processes each request independently, with its output relying solely on the current input and having no recollection of previous interactions. For instance, if an LLM is told, "My name is Alex," and subsequently asked, "What is my name?" in a separate prompt, it will not recall the name Alex. Each function call to the LLM is distinct and independent, devoid of any intrinsic memory of past dialogues.

This design choice, while simplifying the core model, means that for AI applications like chatbots to maintain coherent multi-turn conversations, external mechanisms must be employed to simulate memory.

graph TD

A[User Input

x] --> B(LLM: y = f_θ x)

B --> C[LLM Output

y]

style B fill:#f9f,stroke:#333,stroke-width:2px

style A fill:#ccf,stroke:#333,stroke-width:2px

style C fill:#cfc,stroke:#333,stroke-width:2px

subgraph LLM Mechanism

D[Fixed Parameters

θ] --> B

end

subgraph No Intrinsic Memory

E[Previous Input

x_prev] -.X.-> B

end

classDef default fill:#eee,stroke:#333,stroke-width:1px;

linkStyle 3 stroke-dasharray: 5 5;

x is processed independently by f_θ, with no

internal link to previous inputs.

The Core Problem: Building Memory Around LLMs

The stateless nature of LLMs presents a "deadlock" for generative AI applications. Without the ability to recall past interactions, a chatbot would offer a frustrating user experience, requiring constant repetition of context. Building truly intelligent and conversational AI agents thus necessitates external memory solutions.

The Context Window: The LLM's Eyes

A crucial concept in building memory around LLMs is the context window.

The context window is the maximum amount of text, measured in tokens, that an LLM can process and "read" at one time to generate a response. A token is a basic unit of text, which can be a word, a sub-word, or a character, depending on the LLM's tokenizer.

Imagine the context window as the lens of a camera, determining how much of the "scene" (text) the LLM can "see" and comprehend simultaneously. A larger lens allows it to "see" more.

Modern LLMs boast impressively large context windows, ranging from 128,000 tokens to even 1 million tokens in advanced models like Gemini. This significant capacity allows for feeding substantial amounts of text - equivalent to hundreds of pages of documents - as part of the input prompt.

The ability to provide a considerable volume of tokens as input is fundamental for developing external memory mechanisms, as it allows developers to inject conversational history or other relevant data directly into the LLM's current prompt.

In-Context Learning: An Emergent Ability

Beyond their vast parametric knowledge (the knowledge embedded within their fixed parameters during training), larger LLMs exhibit an emergent ability called in-context learning.

- This means LLMs can leverage information and patterns directly present within the current prompt itself to generate an answer.

- Practical Implication: Even if an LLM has never encountered specific, private data during its initial training, if that data (e.g., a multi-page document) is provided as part of the prompt, the LLM can "learn" from its content and answer questions based solely on that provided context.

- Role in Memory: This capability is pivotal for designing external memory systems. By strategically injecting relevant past information into the current prompt, developers can essentially "teach" the LLM about previous interactions, enabling it to maintain continuity.

Simulating Short-Term Memory: The Conversation Buffer

To overcome the inherent statelessness and provide chatbots with a sense of "memory" within a single conversation, the most common approach is to simulate short-term memory using the conversation history.

Since LLMs rely on the information provided in the current prompt, the solution is straightforward: concatenate the entire conversation history into every new prompt sent to the LLM.

How Chatbots Implement Short-Term Memory

- Leveraging the Context Window: The large context windows of modern LLMs are critical here. They allow for the entire conversation history, even relatively long ones, to be packaged and sent as a single input without exceeding token limits for typical interactions.

-

The "Conversation Buffer": In practice, this involves

maintaining a list or similar data structure of

messages (user inputs and LLM outputs).

- Every user input is appended to this list.

- Every LLM output is also appended to this list.

-

This entire

messageslist is then serialized and passed as the "prompt" for subsequent LLM calls. -

This dynamic

messagesvariable introduces statefulness at the application layer, even though the LLM itself remains stateless.

graph TD

A[User Input] --> B{Application}

B --> C[Append to Conversation Buffer]

C --> D[Conversation Buffer

List of Messages]

D --> E[Serialize Buffer as Prompt]

E --> F[LLM Call]

F --> G[LLM Output]

G --> B

G --> C

style D fill:#f9f,stroke:#333,stroke-width:2px

style F fill:#cfc,stroke:#333,stroke-width:2px

Characteristics of Short-Term Memory

- Temporary: This type of memory is transient. It exists only within the current session or runtime of the application. If the application or server restarts, this "short-term memory" is lost.

- Conversation-Scoped (or Thread-Scoped): Short-term memory is typically confined to a single "conversation" or "thread." Each new chat session (like opening a new chat in ChatGPT) begins with an empty memory, and only messages within that specific conversation are used to construct its prompts. This prevents prompts from becoming excessively long and incoherent by including irrelevant past interactions.

Limitations of Short-Term Memory

While effective for maintaining basic conversational flow, short-term memory, as implemented through conversation history, has significant limitations that hinder the development of truly intelligent and personalized AI assistants.

1. Short-Term Memory is Fragile

- Problem: This memory is often held in transient variables within the application's runtime. If the application resets, the server crashes, or a new chat session is initiated, all previously stored messages are lost.

- Consequence: The chatbot loses all context of prior conversations, becoming a "stranger" to the user, leading to a fragmented and frustrating user experience.

- Partial Solution: Implementing persistence by storing conversation history in a database (e.g., a relational database or NoSQL store). Each conversation thread gets a unique ID, and messages are stored and retrieved based on this ID. This ensures memory survives restarts but doesn't solve other issues.

2. The Context Window Problem

- Definition: The context window is the finite limit on how many tokens an LLM can process.

- Problem: In prolonged conversations, the accumulated message history, when tokenized, can exceed the LLM's fixed context window size.

- Consequence: When the input exceeds the context window, the LLM may be forced to truncate the input, leading to loss of crucial context from older messages, resulting in incoherent replies or "hallucinations" (generating irrelevant or factually incorrect information).

Solutions for Context Window Overflow:

- Trimming (Blunt & Efficient): The simplest method involves sending only the most recent 'N' messages or the latest 'K' tokens to the LLM. While efficient, this can lead to a significant loss of important context from older parts of the conversation.

- Summarization (Intelligent & Lossy): A more sophisticated approach uses another LLM to summarize older portions of the conversation into a concise representation of past context. This summary is then combined with the most recent messages to fit within the context window. This maintains more context than trimming but is still a lossy process, as some detail is inevitably lost in summarization.

Context Window Overflow Solutions

| Solution | Description | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trimming | Only include the 'N' most recent messages or 'K' most recent tokens. | Simple to implement, computationally inexpensive. | Significant loss of older, potentially critical, context. |

| Summarization | Use an LLM to summarize older parts of the conversation, then include the summary with recent messages. | Retains more relevant context than trimming. | Computationally more expensive, still lossy, potential for summary hallucination. |

3. Short-Term Memory is Thread-Scoped

This is arguably the most significant limitation, fundamentally restricting the ability to create continuously learning and highly personalized AI assistants.

Key Consequences:

- Loss of User Continuity Across Conversations: The LLM does not remember user preferences, style, or past interactions across different conversation threads. For example, if a user specifies a preferred programming language in one chat, the LLM will forget this preference when a new chat is initiated. This severely limits personalization.

- Learning Never Compounds Over Time: The LLM cannot evolve its understanding of a user's unique style, preferences, or recurring problems over multiple, separate interactions. Every new conversation effectively starts from scratch regarding the user's specific context.

- Cross-Thread Reasoning is Impossible: The LLM cannot draw insights or reference information from previous, distinct conversations to inform or assist in a current one. This makes handling complex, multi-session tasks - where context from prior interactions is essential - extremely difficult.

Overall Impact: These limitations highlight the need for a more robust and intelligent memory system - a long-term memory - that can selectively store stable, useful, and reusable information beyond the confines of a single conversation or session.

Why We Need Long-Term Memory

To build truly intelligent and adaptable AI agents, information must persist beyond a single conversation, session, or even days or weeks. This "special type" of information establishes continuity for the system, allowing it to provide personalized, efficient, and evolving interactions.

Long-term memory (LTM) is essential for retaining:

- User Identity and Preferences: Who the user is (e.g., profession, role), their preferred communication style, and recurring constraints (e.g., a specific budget for tasks).

- System Behavior and Adaptation: How the system is expected to behave for that specific user, what approaches tend to work, and what usually fails.

- Past Decisions and Processes: What decisions were made, what solutions were implemented, and the outcomes of previous actions.

Crucially, this new memory type must be selective. Only information that proves to be stable, consistently useful, and reusable across multiple interactions should be retained. Transient or irrelevant conversational "noise" should naturally fade away. This persistent and selective memory is what defines Long-Term Memory (LTM), distinguishing it from the temporary nature of short-term memory.

Three Types of Long-Term Memory (LTM) in LLM Systems

Human cognition categorizes long-term memory into distinct types, and AI systems can emulate this for more nuanced recall.

-

Episodic Memory: "What Happened?"

- What it stores: Recollections of past events, specific actions, and experiences, often tied to a particular time, place, or context. It's about remembering "episodes" from the past.

- Examples: "The user rejected solution A in the last session," "A deployment failed due to missing credentials on Tuesday," "This specific user approval plan was utilized for project X."

- Purpose: Helps the current conversation by recalling past occurrences, informing decisions, and avoiding repetition of past mistakes. It answers questions like, "What did we do last time?" or "Have we tried this already?"

-

Semantic Memory: "What is True?"

- What it stores: Factual knowledge, general concepts, and stable information that is not linked to a specific event. This often includes user-level or system-level facts.

- Examples: "User prefers Python for scripting," "The user is a beginner in data science," "The system uses PostgreSQL as its primary database," "There is a budget constraint of $5,000 for all marketing campaigns."

- Purpose: Provides stable background context about the user, system, or environment. It answers questions like, "What do we know about this user?" or "What constraints always apply?" This is the most common form of LTM integrated into products.

-

Procedural Memory: "How to Do Things?"

- What it stores: Knowledge of strategies, rules, learned behaviors, and "how-to" information for accomplishing tasks. It's about remembering skills and processes.

- Examples: "When solving SQL problems for this user, always avoid subqueries," "If tool X fails, consistently try tool Y as a fallback," "For this user, always explain complex concepts step-by-step," "The preferred workflow for deploying new features involves a pre-approval from the lead architect."

- Purpose: Enables the AI agent to learn and adapt its behavior over time, making it more effective and user-friendly. It answers questions like, "What approach usually works?" or "How should I behave in this situation?"

How Long-Term Memory Works: A Four-Step Process

Implementing long-term memory in LLM systems requires a sophisticated architecture that orchestrates the entire lifecycle of memory, from creation to injection. This process typically involves four key steps:

Step 1: Creation/Update

- Goal:

- To determine which information, if any, from the current interaction is valuable enough to remember beyond the immediate conversation.

- Inputs:

- This step analyzes all relevant data from the interaction: user messages, the LLM's responses, and the outcomes of any tools or external functions used by the AI agent.

- Process:

-

- Extract Memory Candidates: Identify potential pieces of information that might be worth remembering.

- Filter Noise: Discard irrelevant or transient conversational details, focusing on stable facts, preferences, or key events.

- Decide Scope: Determine if the memory is specific to the user, the agent's behavior, or the overall application.

-

Decision Point: Based on predefined rules or

another LLM's evaluation, decide whether to:

- Create a completely new memory (e.g., a new user preference).

- Update an existing memory (e.g., modify a user's skill level).

- Ignore the information altogether if it's not deemed valuable for long-term retention.

Step 2: Storage

- Goal:

- To durably and persistently store the identified long-term memories.

- Actions:

-

- Write Memory: Store the extracted and filtered memory content into a chosen persistent storage solution.

- Assign Identifiers & Metadata: Attach unique IDs, timestamps, and other relevant metadata (e.g., associated user ID, conversation ID, memory type) to facilitate future retrieval.

- Ensure Persistence: The storage mechanism must guarantee that memory survives application restarts, server crashes, and extended periods.

- Storage Types:

- The choice of storage depends on the

type and structure of the memory:

- Relational Database (e.g., PostgreSQL, MySQL): Ideal for structured data, semantic facts, and episodic events that fit into predefined schemas.

- Key-Value Store (e.g., Redis, DynamoDB): Suitable for simple semantic facts or user preferences.

- Log Files: Can be used for raw event data, though less efficient for direct retrieval.

- Vector Database (e.g., Pinecone, Weaviate, Chroma): Crucial for semantic memory. Memories are converted into high-dimensional numerical representations (embeddings) and stored as vectors. This enables highly efficient semantic search, allowing retrieval of information based on conceptual similarity rather than exact keyword matches.

Step 3: Retrieval

- Goal:

- To intelligently identify and retrieve the most relevant past memories for the current conversational context.

- Process:

-

- Analyze Current Context: Examine the current user input, conversation history (short-term memory), and ongoing task.

- Determine Need: Decide if external long-term memory is required to adequately respond to the current query.

- Search Memory Stores: Query the various memory stores. For semantic memory, this often involves converting the current query into an embedding and performing a vector similarity search in the vector database to find conceptually related past memories.

- Select Relevant Subset: From potentially many retrieved memories, select a small, highly relevant subset that will best inform the LLM's response.

- Key Point:

- Retrieval is selective, not exhaustive. Flooding the LLM's context window with too much (even if relevant) information can lead to "context window bloat" and reduced performance.

Step 4: Injection

- Goal:

- To integrate the retrieved long-term memories into the LLM's current understanding for generating a coherent response.

- Process:

-

- Insert into Short-Term Memory: The retrieved long-term memories are inserted into the LLM's short-term memory (the conversation buffer).

- Become Part of Prompt: They become part of the overall prompt that is constructed and sent to the LLM.

-

LLM Perception: The LLM perceives these retrieved

memories simply as additional input tokens within its context

window. It doesn't distinguish between 'new' input and 'retrieved

memory'; it processes everything as the current

x.

- Important Note:

- Long-Term Memory systems do not directly alter the LLM's parameters. They always mediate through the LLM's context window.

graph TD

A[User Query & Short-Term Memory] --> B{Agentic Orchestrator}

B -- "Evaluate & Decide Memory Need" --> C{Memory System}

subgraph Memory System

C --> D[1. Creation/Update]

D --> E[2. Storage

Vector DB, SQL DB, etc.]

F[3. Retrieval] --> B

E -- "Persist Memories" --> E

C -- "Query for Relevant Memories" --> F

end

F --> G[4. Injection: Insert into Prompt]

G --> H[LLM Call

Prompt with Injected LTM]

H --> I[LLM Response]

I --> B

B --> J[User]

style A fill:#ccf,stroke:#333,stroke-width:2px

style J fill:#ccf,stroke:#333,stroke-width:2px

style B fill:#f9f,stroke:#333,stroke-width:2px

style H fill:#cfc,stroke:#333,stroke-width:2px

Challenges and Tools for Memory Systems

Building robust long-term memory systems for LLMs is not without its complexities.

Key Challenges:

- Deciding what is worth remembering: Distinguishing genuinely valuable, stable information from the constant flow of conversational noise and transient details. This often requires sophisticated heuristics, additional LLM calls for evaluation, or human feedback loops.

- Retrieving the right memory at the right time: Ensuring accurate and timely recall of relevant information, especially from large memory stores. A false positive (retrieving irrelevant memory) can lead to incoherent responses, while a false negative (failing to retrieve crucial memory) can negate the purpose of LTM.

- Orchestrating the entire system: Managing the intricate complexity of multiple moving parts - memory creation, diverse storage solutions, intelligent retrieval strategies, and seamless injection - within a broader agentic AI system.

Tools and Libraries for Memory Systems:

Fortunately, a growing ecosystem of tools and libraries is emerging to abstract away much of this underlying complexity, allowing developers to focus on application logic rather than low-level memory management.

-

LangChain's Memory Modules: As part of the LangChain

framework, these modules offer various memory types (e.g.,

ConversationBufferMemory,ConversationSummaryMemory,VectorStoreRetrieverMemory). They provide core memory APIs and management tools that help agents learn, adapt, extract information, and optimize behavior. - Mem0: Positioned as a universal, self-improving memory layer for LLM applications, Mem0 aims to offer personalized AI experiences by simplifying the integration of long-term memory.

- Supermemory: Offers a long-term memory API designed for personalizing AI applications, emphasizing blazing-fast and scalable memory solutions.

These managed solutions and libraries significantly lower the barrier to entry for implementing sophisticated memory capabilities in generative AI applications.

The Future of Memory in LLMs

The current generation of Large Language Models inherently lacks their own default or intrinsic memory. This fundamental absence is the root cause of many challenges faced when building effective and persistent AI applications.

However, this is an active area of research. Significant efforts are underway to develop LLMs with their own internal memory mechanisms, aiming to reduce or even eliminate the reliance on complex external memory systems. Projects like Google's "Titans + MIRAS" are exploring transformer architectures that integrate long-term memory directly into the model itself. The ultimate goal is to enable LLMs to manage their own context and recall information over extended periods, fostering more seamless and natively intelligent interactions.

Regardless of whether memory is external or eventually intrinsic, it remains a critical component for the future development of powerful Generative AI and Agentic AI applications. The ability for an AI to remember, learn, and adapt based on past interactions is paramount to achieving truly intelligent and personalized digital companions.

Conclusion

Large Language Models, while incredibly powerful, are fundamentally stateless at inference. This means they possess no intrinsic memory of past interactions. To overcome this, developers have engineered sophisticated external memory systems. Short-term memory, typically implemented by concatenating conversation history into the LLM's context window, provides conversational coherence but suffers from fragility and limitations regarding context window size and cross-conversation continuity.

Long-term memory systems - comprising episodic, semantic, and procedural memory - address these limitations by selectively storing and retrieving stable, reusable information across sessions. These systems operate through a four-step process of creation/update, storage (often leveraging vector databases for semantic search), intelligent retrieval, and strategic injection into the LLM's prompt. While challenging to build, specialized tools and ongoing research into intrinsic memory promise to make AI agents increasingly intelligent, personalized, and truly memorable.

Further Reading

- Transformer Architectures: Explore the foundational neural network architecture behind most modern LLMs.

- Vector Databases and Embeddings: Understand how text is converted into numerical representations and stored for semantic search.

- Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG): Learn how external knowledge bases are used to enhance LLM responses.

- Agentic AI Systems: Delve into how LLMs are orchestrated with tools and memory to perform complex tasks.

- Context Window Management Strategies: Investigate advanced techniques for handling long contexts in LLMs.