Mastering Context: The Cornerstone of Advanced AI Agent Performance

Mastering Context: The Cornerstone of Advanced AI Agent Performance

In the rapidly evolving landscape of artificial intelligence, Large Language Models (LLMs) have demonstrated remarkable capabilities. However, their true potential is unlocked when these models are integrated into AI agents capable of maintaining coherence, learning from interactions, and performing complex, multi-step tasks. The critical challenge in building such agents lies in effectively managing their "memory" - the information they can access and process at any given moment. This discipline is known as Context Engineering.

What is Context Engineering?

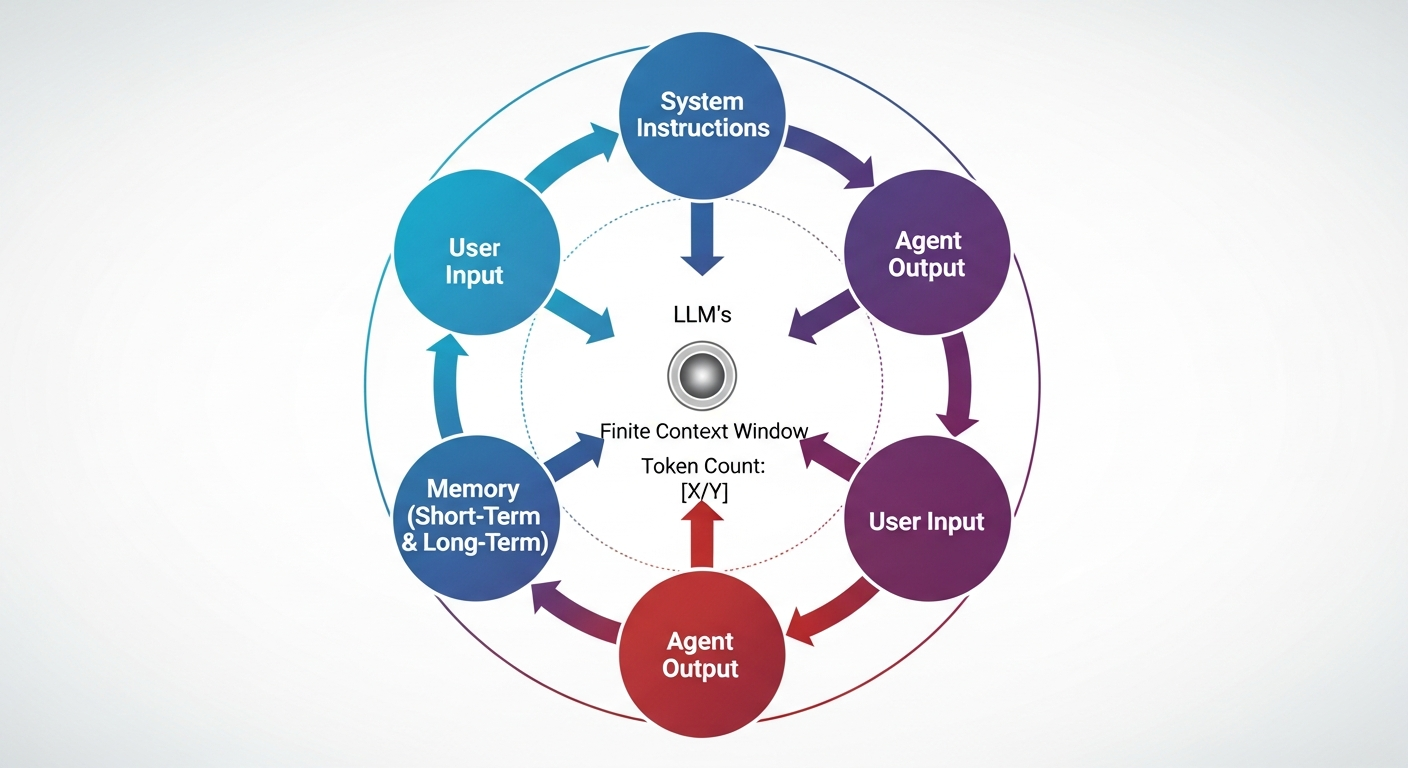

Large Language Models (LLMs) are sophisticated AI models trained on vast datasets, enabling them to understand, generate, and process human language. Their ability to process information is constrained by a context window, which refers to the maximum amount of text, in tokens, that the model can consider or "remember" at any one time. A token is the fundamental unit of text that an LLM processes; it can be a word, part of a word, or punctuation.

Context Engineering is the art and science of efficiently managing this finite context window. It goes beyond simply crafting effective prompts - a practice known as Prompt Engineering. While prompt engineering focuses on optimizing a single input to an LLM for a specific response, context engineering is a broader discipline that designs the entire information environment an LLM operates within. It ensures that at every step of an agent's operation, the context window is filled with only the most relevant, high-signal information needed for the task at hand.

This comprehensive approach encompasses several key components:

- Prompt Engineering: Structuring clear and effective instructions.

- Structural Outputs: Defining how the agent should format its responses.

- Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG): A technique that allows LLMs to retrieve and incorporate new information from external knowledge bases before generating a response, thereby grounding answers in up-to-date and specific data. This helps reduce AI hallucinations and the need to retrain models with new data.

- State and History Management: Maintaining a coherent understanding of past interactions and ongoing tasks.

- Tool Integration: Enabling the agent to use external tools and APIs.

These elements collectively shape what the LLM processes and understands, making context engineering vital for building robust and reliable AI agents.

Why Context Engineering Matters: The Challenge of Finite Context

The context window is a precious, finite resource. Its effectiveness diminishes with repeated use, especially in long-running or tool-heavy applications. Without diligent management, AI agents can suffer from token bloat - an excessive accumulation of tokens that inflates operational costs and degrades performance. This "bloat" can lead to several critical failure modes:

Problem: LLMs Get Lost

A fundamental issue with LLMs in multi-turn interactions is their tendency to lose context. Without proper memory management, agents can become repetitive, forget earlier details, and lack a sense of continuity. This is akin to a human repeatedly asking the same question or forgetting previous decisions. Implementing robust agent memory allows the agent to recall original goals, reference past actions, and maintain an intelligent, reliable flow throughout a conversation or task.

Context Failure Modes

To highlight the importance of effective context engineering, it's crucial to understand the common ways context can fail:

-

Context Burst: A sudden, uncontrolled increase in

tokens from one or multiple components, such as verbose tool outputs or

extensive RAG retrievals. This can quickly exhaust the context window

and incur high costs.

-

Example: An agent calls a

get_orderstool, which returns a large JSON payload with many irrelevant fields, causing a spike in token usage.

-

Example: An agent calls a

-

Context Conflict: Occurs when contradictory or strongly

conflicting pieces of information coexist within the context, leading to

confusion and unreliable outputs.

- Example: Conflicting instructions in the system prompt and few-shot examples, or overlapping tool definitions that make it ambiguous which tool to use.

-

Context Poisoning: Incorrect or misleading information

enters the context (e.g., through flawed summaries, lossy compression,

or inaccurate memory objects) and contaminates the agent's understanding

in subsequent turns, potentially leading to hallucinations.

- Example: A summarization step accidentally misinterprets a key detail, and this incorrect summary is then used as a basis for future reasoning.

-

Context Noise: Redundant or overly similar items (e.g.,

many near-duplicate tool definitions or excessive retrieved documents)

clutter the context, making it difficult for the model to identify and

focus on the truly relevant information.

- Example: Loading definitions for hundreds of tools when only a few are needed for the current task, or retrieving too many similar documents from a knowledge base.

Core Principles of Context Engineering

The overarching goal is to always aim for the smallest, highest-signal context possible. This maximizes the likelihood of the desired outcome by providing the LLM with focused, relevant information while minimizing cost and processing overhead.

Key strategies for achieving this include:

- Reshape & Fit: Actively managing the size and content of the context.

- Isolate & Route: Directing specific context to specialized components or subagents.

- Extract & Retrieve: Systematically storing and retrieving information from memory.

Prompt & Tools Hygiene

Maintaining a "clean" context begins with good hygiene practices:

- Keep system prompts lean, clear, and well-structured.

- Use small, canonical few-shot examples only when they demonstrably add value.

- Minimize overlapping tools and implement robust tool selection mechanisms to prevent confusion and reduce token overhead.

Context Engineering Techniques: Managing Memory

Context engineering techniques are broadly categorized based on their application duration: Short-Term Memory (In-session) and Long-Term Memory (Cross-session).

Short-Term Memory (In-session)

These techniques focus on optimizing the context window during an active interaction, ensuring the model's focus and efficiency.

1. Reshape & FitThis strategy involves dynamically adjusting the size and content of the conversation history to fit within the context window and maintain focus.

-

Context Trimming:

- Definition: The simplest technique, where older turns (user/assistant message pairs, including tool calls and results) are progressively dropped, retaining only the most recent 'N' turns.

- Problem Solved: Directly addresses context limits, reduces noise, and prevents the agent from getting lost in lengthy conversations.

- Benefits: Ensures fresh context, improves model attention, and speeds up processing by keeping the input concise.

-

Context Compaction:

-

Definition: Similar to trimming but more targeted.

It specifically drops verbose

tool_callandtool_resultsoutputs from older turns while preserving essential user/assistant messages and tool placeholders. - Problem Solved: Particularly effective for "tool-heavy" agents where tool outputs can quickly dominate the context, causing noise and bloat.

- Benefits: Achieves fresh context, better attention, and faster processing by significantly reducing token count while retaining the semantic signal that a tool was invoked.

-

Definition: Similar to trimming but more targeted.

It specifically drops verbose

-

Context Summarization:

- Definition: Compresses older messages into a concise, structured summary that is then injected back into the conversation history. The most recent 'N' turns are typically kept verbatim for immediate context.

- Problem Solved: Addresses context limits and noise while striving to preserve key information from older interactions, unlike trimming which discards it.

- Benefits: Provides a "golden summary" - a dense object capturing the essence of past conversation, improving long-range recall and maintaining context over extended interactions.

| Feature | Context Trimming | Context Summarization |

|---|---|---|

| Latency / Cost | Lowest (no extra model calls) | Higher at summary refresh points (requires model calls) |

| Long-Range Recall | Weak (hard cut-off, information is lost) | Strong (compact carry-forward of key information) |

| Risk Type | Context loss (important details might be discarded) | Context distortion/poisoning (summaries can misinterpret or hallucinate) |

| Observability | Simple logs (which messages were kept/dropped) | Must log summary prompts/outputs (to understand summary content) |

| Eval Stability | High (clear rules for what's kept) | Needs robust summary evaluations (to ensure accuracy) |

| Best For | Tool-heavy ops, short workflows, temporary info | Analytics/concierge agents, long threads, dependent tasks |

Heuristics for Trimming/Compaction:

- Analyze Sessions: Use feedback (e.g., "thumbs-down") to identify when context issues occur.

- Track Metrics: Monitor average token size, tasks per session, and token size per turn.

- Maintain Turn Blocks: Do not trim mid-turn; always keep a user message and its agent responses/tool usage together to avoid losing coherence.

- Proactive Management: Set thresholds (e.g., 40% and 80% of context window) to trigger trimming/compaction before limits are hit. Control tool outputs by compacting or summarizing them.

- Monitor "Tokens Saved": Quantify the cost benefits of these strategies.

This technique involves delegating specific tasks and their associated context to specialized subagents.

-

Context and Tool Offloading to Subagents:

- Definition: Instead of one monolithic agent handling everything, complex tasks are broken down and handed off to subagents specialized in particular functions. The context passed to a subagent is precisely scoped to what it needs, avoiding the transfer of irrelevant historical data.

- Problem Solved: Minimizes context conflicts, reduces token bloat in multi-agent systems, and ensures a fresh, isolated context for reasoning.

- Benefits: Improves reasoning focus, enhances modularity, and reduces the likelihood of subagents getting confused by a parent agent's irrelevant conversational history.

Long-Term Memory (Cross-session)

These techniques focus on building continuity and personalized experiences across multiple sessions or extended periods.

Extract & RetrieveThis strategy involves systematically storing and retrieving relevant information to enrich ongoing interactions.

-

Memory Extraction:

- Definition: The process of identifying and saving critical information from interactions into a structured memory store. This could involve defining a JSON schema for memory objects, using typed save functions, or leveraging formats like Markdown for human-readable and structured records.

- Shape of a Memory: Memories should be structured to preserve determinism and capture key details. They should evolve from simple forms to more complex structures as needed, always prioritizing information a human would naturally remember, balancing verbosity and structure.

- Memory-as-a-tool: This concept treats memory storage and retrieval as explicit actions an agent can take, similar to calling any other tool.

-

State Management for Context Personalization:

- Definition: Defining a persistent state object (e.g., a JSON blob) that contains crucial information about the agent's goal, the user, the current ticket, priority, and other relevant metadata. This state is then injected into the system prompt across multiple turns, providing continuous, personalized context.

- Benefits: Enables highly personalized interactions, maintains continuity over long-running tasks, and allows agents to remember user preferences or ongoing issues across sessions.

-

Memory Retrieval:

-

Definition: The process of enriching each agent

turn with the right context before responding. This typically

involves:

- Memory Check: Determining if historical context is needed.

- Retrieval from Stores: Accessing a long-term store (e.g., a traditional database for facts, preferences, logs) and a vector database for semantic search of related conversations or examples. A vector database stores information as numerical representations (embeddings) that can be quickly queried for similarity.

- Filtering, Ranking, and Injection: Selecting, prioritizing, and injecting the most relevant context into the LLM's prompt.

- Memory-as-a-tool: The agent can explicitly decide when and how to retrieve information, making memory an active component of its reasoning.

-

Definition: The process of enriching each agent

turn with the right context before responding. This typically

involves:

Real-World Application: Context Lifecycle in Action

Consider an IT troubleshooting agent designed to assist users. In a typical interaction:

- Initial Query: A user reports "laptop fan making noises during games." The agent responds with an opening query, and the initial context usage is minimal.

-

Context Burst Demonstration:

- The user then asks to see orders using a specific order ID (e.g., ORD-12345).

-

The agent performs a

get_orderstool call, which returns detailed order information. - This tool output, especially if verbose, causes a significant increase in "Agent Output" and "Tools" token counts, demonstrating a context burst.

- Subsequently, the user asks for the refund policy for a "MacBook Pro 2014."

-

The agent calls a

get_refundtool, which provides a detailed refund policy. - A visualization (e.g., a "Context Lifecycle graph") would show a sharp spike in tokens during turns with tool calls, potentially rising from a few hundred to several thousand tokens. This clearly illustrates the impact of unmanaged tool outputs.

flowchart TD

Start(User starts new session: Laptop fan noise) --> A[Agent: Initial Query & Context Load]

A --> B{User: Show orders for ORD-12345}

B --> C[Agent: Calls get_orders tool]

C --> D[Tool: Returns large Order Details payload]

D -- High Token Count --> E{Context Burst Occurs!}

E --> F{User: Refund policy for MacBook Pro 2014}

F --> G[Agent: Calls get_refund tool]

G --> H[Tool: Returns Refund Policy text]

H -- Another Token Spike --> I{Context Window Nears Limit / Potential Noise}

I --> J[Agent: Responds to user]

J --> End(End of Interaction)

Context Profiles of AI Agents

Different agent types have distinct context management needs:

- RAG-heavy Analyst: Context is primarily dominated by retrieved knowledge and citations.

- Tool-heavy Workflow (Automation/Ops Agents, CRM): Context is dominated by frequent tool calls and their returned payloads. A wide variety of tools increases the risk of context confusion and bloat.

- Conversational Concierge (Planning, Coaching): Context is dominated by a growing dialogue history, and assistant-token usage scales with session length. These agents often require long, coherent responses.

Dynamic vs. Static Context Management

The context an LLM processes can be split into stable and variable components:

| Category | Static Context (Fixed Tokens) | Dynamic Context (Variable Tokens) |

|---|---|---|

| System Identity | System instructions (role, rules, agent identity) | N/A |

| Capabilities | Tool definitions (unchanged, always available) | Tool results (unpredictable volume, increase uncertainty) |

| Guidance | Examples (optional few-shot prompts, included if valuable) | Retrieved knowledge (unpredictable volume, driven by semantic similarity) |

| Memory | N/A | Memories (short-term/long-term formats, total tokens fluctuate) |

| Interaction | N/A | Conversation history (assistant outputs, user inputs) |

Dynamic tokens are the primary target for context engineering, as they are highly controllable and directly impact cost and performance.

Cross-Session Memory: Enabling Personalized Interactions

One of the most powerful applications of context engineering is enabling cross-session memory injection. This involves:

- Summarizing Previous Sessions: After a session, the conversation history is summarized into a structured format, similar to the "golden summary" described earlier.

-

Injecting into New Sessions: This summarized context is

then injected into the system prompt of a new session.

- Example: An agent with cross-session memory enabled might greet a user by saying, "Are you still having issues with your MacBook's internet connection after the macOS Sequoia update?" - directly referencing a past problem.

This capability leads to:

- Highly personalized and context-aware interactions.

- Efficient token management and cost reduction.

- Maintained conversational focus across turns.

-

Improved factual consistency and reduced hallucination

through explicit rules in

SUMMARY_PROMPT(e.g., contradiction checks, temporal ordering, privacy guardrails).

Best Practices in Context Engineering

Prompting to Avoid Context Conflict and Noise

- Be explicit and structured: Use clear, direct language. Instructions should be specific enough to guide action but flexible enough to allow for reasoning.

- Give room for planning and self-reflection: Avoid micromanaging. Allow the model space to choose tactics. Encourage lightweight reflection (e.g., "List 1-3 checks before finalizing").

- Avoid Conflicts: Keep the toolset small, non-overlapping, and unambiguous. If a human can't easily distinguish between tools, an LLM likely won't either. Be cautious with conflicting instructions or examples.

- Choose the right tools: More tools do not always mean better outcomes. Favor targeted tools over general ones and combine related operations into richer tools. Each tool's purpose should be distinct to avoid overlap and distraction.

- Return meaningful context from tools: Ensure tool outputs are high-signal and semantically useful, preferring human-readable identifiers. Avoid returning excessive or redundant data.

General Best Practices in Agent Memory

- Understand Your Context: Clearly define what constitutes a "meaningful memory" for your specific agent and use case.

- Tailor Your Strategy: Decide when and how to remember and forget information. Promote stable, reusable facts while actively pruning temporary or low-confidence data.

- Evolve Memories: Continuously optimize memory distillation, consolidation, and injection steps. This includes cleaning, merging, and consolidating memories over time.

- Perform Evaluations (Evals): Systematically measure the impact of memory by comparing agent performance with memory enabled versus disabled. Develop memory-specific evaluations for long-running tasks and complex contexts, focusing on metrics like recall accuracy, context retention, and consistency.

Scaling and Advanced Concepts

Libraries and Tools

The OpenAI Agents SDK provides a solid foundation for implementing context engineering techniques such as trimming, compaction, and summarization within sessions. It offers flexibility for custom session management and building agentic applications. Other evolving libraries and frameworks also offer capabilities for building hierarchical memory graphs and integrating vector databases for contextual recall.

Evaluation and Measurement

Measuring the effectiveness of memory features is crucial:

- Comparative Evaluation: Run regular evaluations with memory enabled and disabled to quantify performance improvements.

- Memory-Based Evals: Create specific evaluations for long-running tasks or conversations, focusing on metrics like completeness, quality of summaries, injection time, and effectiveness of the injection prompt.

- Golden Dataset: Prepare a "golden dataset" (e.g., 50 annotated examples) for rigorous testing.

- Heuristic Tuning: Experiment with different parameters for trimming and compaction to find the optimal balance.

Hierarchical Contexts

The concept of hierarchical contexts is gaining traction. This involves differentiating between various scopes of memory:

- Global Memory: Stores information consistently relevant to the user or agent (e.g., user preferences, persona details). This acts as a long-term, persistent knowledge base.

- Session Memory: Holds context relevant only to the current interaction or task.

- Task/Project Memory: Can be implemented to store information specific to an ongoing project or sub-task, nested within session memory.

Over time, important session memories can be "graduated" into global memory. This tiered approach ensures the agent uses the right context at the right time without mixing up irrelevant details.

Keeping Memory Fresh and Pruned

To prevent memory overload, agents need strategies to manage the freshness of information:

- Temporal Tags: Attach timestamps to memories to track their age, allowing the model to prioritize recent information.

- Memory Overwriting/Consolidation: Newer, more relevant instructions or facts can override older, stale memories. Techniques like ReasoningBank distill and organize generalizable reasoning strategies from successful and failed experiences, ensuring memory is continuously updated.

- Weighted Average/Window Functions: Focus the agent's attention more on recent memories and gradually downgrade the importance of older ones.

- Pruning: Regularly remove memories that are no longer important to the agent's current function or goals. The specific pruning strategy should align with how quickly memories become irrelevant for the agent's use case.

Scaling Agent Memory Systems

Managing memory for many users with individual and shared memory pools requires a robust data management strategy:

- Memory as a Tool vs. Stored Data: Distinguish between memory actively used for retrieval/search (often in vector databases) and memory stored for persistence (e.g., summaries).

- Retrieval Systems: Utilize vector databases for efficient similarity search of long-term memories. Scaling techniques include sharding, optimizing embedding models, and refining retrieval processes.

- Data Storage: Focus on efficient storage and management of large volumes of text-based information.

- Pilot Approach: Introduce new memory management techniques to a subset of users first to observe their impact before a wider rollout.

- Use Case-Driven Design: The memory system design should be tailored to what the agent needs to remember, how it should remember, and when it should forget. For example, a travel concierge agent might have limited, consistent user preferences, while a life coach requires tracking vast, evolving personal information, demanding more advanced and scalable memory pools.

Conclusion

Context engineering is no longer an optional add-on but a fundamental discipline for building effective and intelligent AI agents. Moving beyond simple prompt optimization, it demands a holistic approach to managing the flow and content of information within an LLM's finite context window. By implementing sophisticated memory patterns - from dynamic trimming and summarization for short-term coherence to structured extraction and retrieval for long-term personalization - developers can create agents that are not only more capable and reliable but also more cost-efficient and less prone to common failure modes like context burst and poisoning. Mastering context management is key to unlocking the next generation of AI agent experiences.

Further Reading

- Advanced Prompt Engineering Techniques

- Designing Multi-Agent Systems

- Vector Databases for Semantic Search

- LLM Evaluation Metrics and Benchmarking

- The Architecture of Persistent AI Agents